Jyotirmai Singh

Physicist, Tinkerer

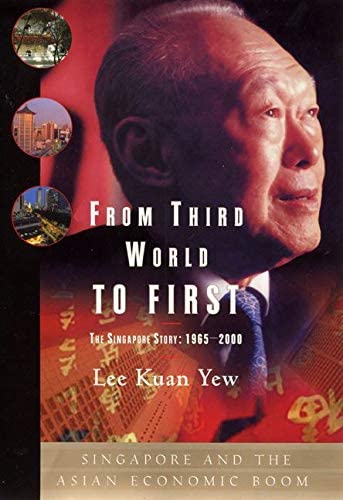

From Third World to First - Part 1, Lee Kuan Yew

For the past few months I’ve been reading Lee Kuan Yew’s memoir From Third World to First: The Singapore Story. This

particular book is of huge interest to me since I personally benefitted from LKY’s nation building experiment in Singapore. I still remember those years somewhat like a dream, so it was extremely fascinating to read what it took to generate such prosperity and turn a tiny island into a global cosmopolitan city state.

The book is split into two halves. Part I addresses the domestic challenges Lee and his colleagues faced after being ejected from Malaysia, and how the built Singapore up. Part II, focuses on Singapore’s neighbors and international partners. That part II is much larger is a very apt metaphor of the reality of this little city state which had to continually keep its much larger neighbors in mind when deciding what to do. This review will just focus on Part I though since that has the most important

lessons that Yew learned on during the grand experiment of creating a nation from scratch.

In part I, Lee shows us the central ingredients behind Singapore’s rise. A consistent theme throughout his writing was the precarious position Singapore was in. Due to its vulnerability, it could not afford to be complacent. It had no bounty of natural resources nor a formidable army to rely on. Lee and his party, the PAP, decided early on that Singapore’s only chance would come by becoming the most efficient government in the region and to train its small population to become highly skilled.

He details many of the key policies that marked his long period as Prime Minister. The first order of business was to establish a strong army that could act as a credible deterrent to its then hostile neighbors Malaysia and Indonesia. From this need arose Singapore’s National Service requirement, whereby all males of a certain age had to serve a period in the army or some other branch. He also hoped that this shared experience of hardship would help to establish a collective Singaporean identity in addition to peoples’ ethnic identities.

Identity was also a huge issue for the young Singapore. Its small population was made up mostly of ethnic Chinese, with minorities of ethnic Malays and Indians. Lee and his team feared that if they could not succeed in creating a common Singaporean identity, ethnic tensions could spiral out of control. This was especially a threat with the Malay and Chinese communities. On this front, Lee explains his decision to adopt English as the official working language as a necessity for social harmony. If any one language were privileged, it could set off a volatile chain of events culminating in riots of the type Malaysia was seeing at the time.

However, he insisted on a bilingual education including both English and students’ own mother tongues so that no one felt their language was being forcibly taken for them. His calculation was that eventually people would realize on their own that learning English was in their interest. Lee believed that English was the language that would open up a world of opportunity for Singaporeans. If they spoke English, they could interact with the multinational corporations that Lee believed Singapore needed to attract to train and put its people to work. He calculated that the rewards of the marketplace would naturally induce people to adopt English in some form.

A key part of Singapore’s success has been its economic model. Lee stressed the need to create “A Fair, Not Welfare, Society”. An example of this is the Singapore Central Provident Fund or CPF. Under CPF, everyone has to put a certain proportion of their salary into a fund for their retirement. Western observers might instinctively go up in arms about how this is theft, but it is a model that has worked well for Singaporean citizens and residents like our family, who contributed happily for years to the CPF. Lee details how the CPF scheme had some flexibility built into it - such as allowing people to invest their contributions in certain cases. If they were able to earn a rate of return higher than the CPF, they could keep the extra. The system is designed to encourage people to work hard but at the same time to protect those who might fall through the cracks - as long as they are willing to dust off and try get back up. Lee views Western welfare states with dismay, arguing that governments have put themselves in a very difficult position by attempting to be the guarantors of society. Not wanting to replicate this model of development was a key element of his thinking.

One of the most criticized aspects of Singapore is its restrictive personal freedoms. Western observers routinely deride Singapore as an authoritarian or pseudo-authoritarian state. Lee does not shy away from such challenges. He argues that an unfettered free press can be a tremendously destabilizing force and is not appropriate in certain contexts. For example, a small state like his could not afford to have a foreign press baron stirring up trouble through a locally owned newspaper like Rupert Murdoch can do in the US. Singapore’s defamation laws are also famous for their harshness, and people can be taken to court for lying. On the one extreme this appears draconian, but on the other it does moderate the destabilization that a rabid unaccountable free press provides. This is a very fine line, and I’m not sure I fully agree with Lee on his approach, but it has worked in the unique context of Singapore. I doubt it could work in a larger country.

Despite this, we should not confuse Singapore with China. Singapore has regular and fair elections. Foreign newspapers are allowed to circulate. The economy is predicated on a free and open exchange with the outside world. Even when Lee had a bone to pick with foreign papers, he did not ban them. He simply reduced their domestic circulation until they published his written response to their articles. I found this to be a very smart tactic since his opponents could not complain about censorship. Lee also noted in his book that the open internet would make the spreading of ideas even more easy, and this could have required a modification of their approach to media.

At the heart of Lee’s approach was a pragmatic attitude. He illustrates how he and his ministers were constantly trying their best to learn from others. Whether it was creating an army with Israeli instruction, or a financial centre with Dutch help, they had the humility to accept aid whenever it was helpful in achieving their goals. There was not much of an ideological element to his plans. He would assess the available information, choose a course of action, and then evaluate it. If it had worked, great. If not, they would modify as necessary. He was never scared to admit he was wrong, and had the humility to change course. I find this quality very admirable, and want to emulate it in my own life.